It was also noteworthy that few researchers identified instances where teachers had attempted to curtail boys’ dominance of school playgrounds. As part of my dissertation I reviewed several international studies of school playgrounds (too many to list here, but I can supply the details to anybody who is interested), and it was clear that the way that boys use school play spaces – typically in ball sports that take up a lot of territory – dominates the overall use of the spaces. Here, Thorne draws a explicit link between boys’ early experience of unchallenged access to play space, and adult men’s later dominance of public spaces in general. For example, there is ample evidence, reviewed and analysed by Nancy Henley, that adult men take up more personal and public space than adult women.” Thorne, 1994, p.83 He wrote: “Boys’ control of space can be seen as a pattern of claimed entitlement, perhaps linked to patterns well documented among adults of the same culture. This is even acknowledged in some councils’ play strategies, often in the context of recognising a lack of corresponding leisure facilities dominated by girls.Įleven years before Thomson’s paper was published Barrie Thorne discussed similar concepts in his 1994 book Gender Play. I am not arguing that the boys themselves actively work to keep out other users – although there are certainly many instances when they do, as this excellent article about Auckland female skateboarder Amber Clyde illustrates – but more that society at large thinks of skate parks as places primarily used by males. The obvious example of interest to me is skate parks, which I contend are territorialised spaces: they’re thought of as spaces where boys and young men practise their skills and spend time with their friends. So, it’s not just a case of those users thinking that the space belongs to them – it’s when everybody else thinks it as well, perhaps even without realising it.

SUBVERT SKATE PARK FREE

I think this implies that the attitudes about who has free access to a space are defined more broadly than just by the users themselves.

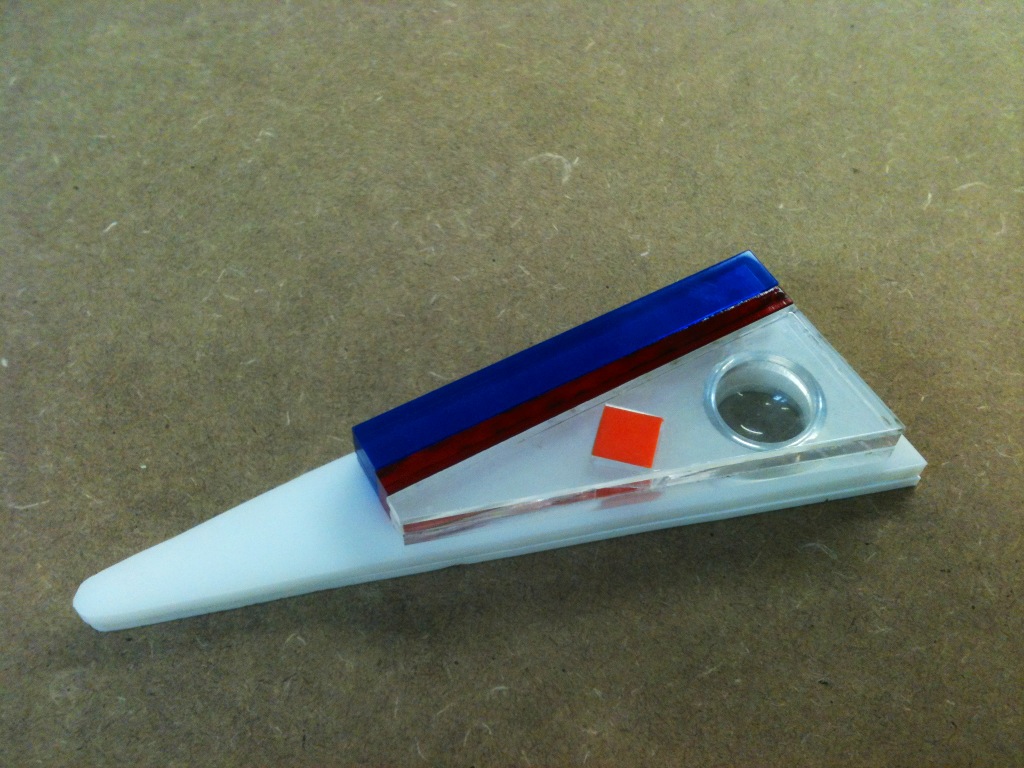

Thomson makes the point that territorialisation occurs when people think of a space as belonging to a certain group. If this is the case, it then becomes a designated or classified area, cleared and maintained for certain activities, where novel conditions might exist and where certain individuals have free or restricted access.” Thomson, 2005, p.64 In other words, think of it as other than neutral. I’ve summarised her definition of territorialisation in my image above, but here’s a further explanation: “One of the first acts of territorialisation occurs when people make judgements about a space and perceive it as significant. I learned this term after reading Sarah Thomson’s 2005 paper Territorialising the primary school playground: deconstructing the geography of playtime. I feel like I may have already used the term ‘territorialisation’ a few times in blog posts and Facebook comments, so I thought it would be useful to explain what I mean by it, and why it’s relevant to my research about gender and play.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)